Adverse childhood experiences and resilience

“…that non-compliant patient is driving me crazy…”

How many times have we said or thought something like that during our busy daily clinic?

Missing appointments, skipping medication doses, continuing ‘bad’ habits that clearly contribute to their poor health outcomes. Why can’t patients get it right?

FRANKFORT During my 20-year OB-GYN practice, I asked all patients at their annual visit if they were smokers. If the answer was ‘yes,’ I would review the medical harms that result from smoking. I wanted to be sure my patients were informed and knew the consequences. One established patient responded that she continued to smoke despite my advice. When she told me that she started smoking at age 10, I questioned what prompted her to start so young. Her father, who hated the smell of cigarette smoke, would leave her alone at night in her bed if she smelled like cigarette smoke. She then told me tearfully that she had taught her eight-year-old sister to smoke. “I was a bad sister-wasn’t I?” In my zeal to stop her ‘bad’ habit, I had completely overlooked why she started smoking. Not only was I not helping her make an informed personal health decision on her smoking, but I was retraumatizing her annually for feeling she was a bad sister. I assured her she was the best sister anyone could want and applauded her skill to figure out how to protect herself and her sister at such a young age. My determination of her smoking as a ‘bad’ habit was actually an intelligent decision by a child to shield herself and her sister where adults had let her down.

Treating the Whole Patient

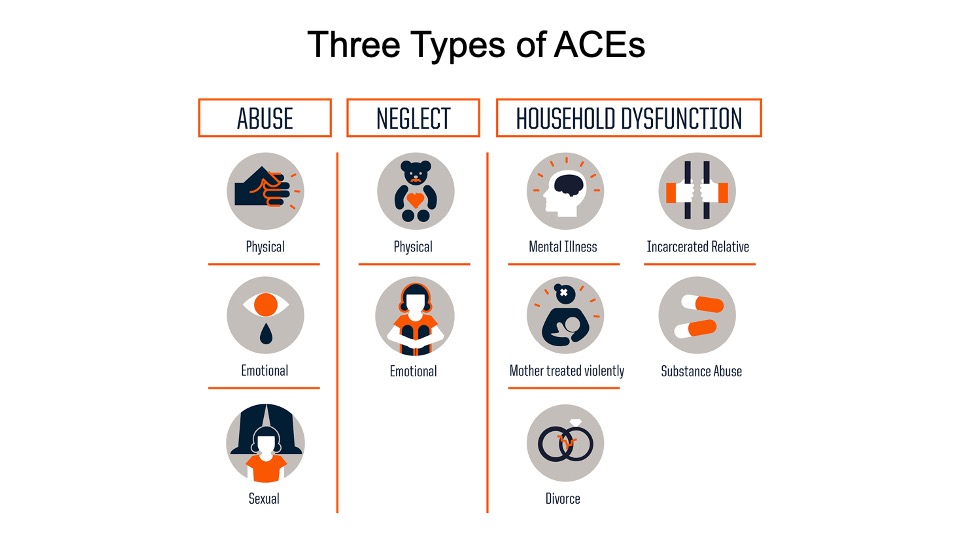

The complexity of a patient’s life experiences, home situation, financial state, interpersonal relationships, and food insecurity all contribute to their behavior in our complex medical world. And sometimes we forget that every patient who enters our exam room with their list of medical symptoms also enters pulling behind them a little red wagon full of adverse childhood experiences that determine their reaction to our medical world and how they will respond to our best intentions to achieve a good health outcome. Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are events that happen before age 18 years old that are a result of neglect, abuse, and household dysfunction and that change the trajectory of brain development as neuropathways are laid down before age two years (Figure 1). Incomplete neuro connections both across and within brain regions can limit the ability of functional areas such as empathy or ability to control impulses and emotions. Continuous fight or flight experiences, leading to toxic stress resulting from a violent or unstable home life as a child, can cause an inflammatory response with high cortisol levels initiating chronic disease early in adulthood. Coping with these childhood stresses can lead to health-risk behavioral choices that prompt social and emotional cognitive impairment, resulting in disease, disability, and social problems. Social-emotional development is based on secure attachment and becomes the foundation for cognitive development and a sense of self-identity. Lack of a stable nurturing relationship with a caregiver that is consistent and caring can influence a child’s health as an adult. There is a risk response curve type reaction of ACE scores and chronic disease: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, alcoholism, stroke, COPD, depression, and suicide, with six or more ACEs resulting in a 20-year early death.

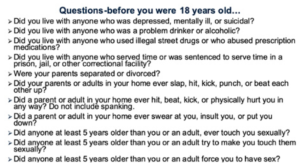

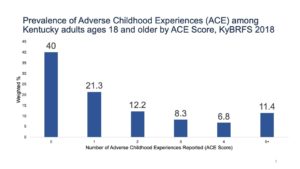

Figure 2 shows the 11 questions in the ACE inquiries used by the Kentucky Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (KyBRFS). These questions were asked of a randomized group of Kentuckians during the annual survey in both 2015 and 2018. Kentucky’s results show one in four adult Kentuckians reported that as children they lived with a family member with mental health issues and were verbally abused as children. One in ten children lived with a family member that was incarcerated or jailed. Figure 3 gives a picture of the percent of patients in our offices that have from zero to five or more ACEs. Scores are also predictors of early age smoking, teen pregnancy, teen paternity, increased number of sexual partners, and sexually transmitted infections, along with multiple other health-risk behavioral choices resulting in patients with higher ACE scores having in higher outcomes of chronic disease.

Newer research shows that not only do these ACEs of childhood contribute to poor health outcomes and early death but the adverse community environments — racism, poor housing, violence, discrimination, poverty — add to these feelings of despair. These effects are seen more often in people living in poverty, marginalized communities, and communities of color. The zip code where a patient lives affects life expectance more strongly than the genetic code.

Positive Childhood Experiences and Resilience Research

Why does one patient with a complex history of historical and generational trauma develop into a person working in the healing community like you and me while another leads an unhealthy life with a poor social living situation and a shorter life expectancy?

Studies in the science of thriving, which look at the positive childhood experiences of patients, show us that a childhood with more positive experiences builds a balance for that patient. These experiences are called positive childhood experiences (PaCEs). Development of these nurturing trusting relationships build that sense of self-worth in the child — it may be a coach at school, a grandparent, a Sunday school teacher, a friend’s parent, a neighbor — someone who showed an interest in that child and showed them that they mattered and that they cared about them. These ideas are intuitive to many of us, but there is now hard science to support and expand our understanding of these positive experiences — the science of thriving — as a key to building that child. Frederick Douglass told us, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

Think ‘What Happened to You?’ Instead of ‘What’s Wrong with You?’

Patients who continuously miss appointments could fear disappointing the medical provider as they haven’t had funds to purchase their medications or transportation to get to the pharmacy. Many patients have a lack of reliable transportation to come to your office or could face repercussions for missed work if they have no sick leave available.

Resilience, and how we achieve it, is discussed often in our society. The foundation of resilience is the combination of

- Supportive nurturing relationships

- Adaptive skill building

- Positive experiences that reinforce self-efficacy, perceived control, and belonging

The way we view our patients and the effects of their past experiences matter. With newer information from the science of thriving, we can help people to learn these skills and support their success instead of continuing to allow them to fail. Our support as trusted healthcare providers and staff can make a difference in the lives they can lead.

Connie White, MD, CHFS, MPH, is deputy commissioner ofclinical affairs at the Kentucky Department for Public Health.

Figures are available online at: CDC Adverse Childhood Experiences Study and Health Consequences www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-SSwYTe8TY