Loss of global productivity is in the billions of dollars

LEXINGTON Over the summer of 2024, major global news outlets including the Wall Street Journal and EuroNews shed light on the growing epidemic of nearsightedness, known also as myopia, in children. Children around the world are being diagnosed with myopia at alarming rates, including nearly 80 percent of young adults in some Asian countries. Here in the US, over the past 40 years, the myopia rate in the population has gone from 25 percent to almost 45 percent. Studies predict that one in every two people will develop myopia by the year 2050, a projected five billion people! Awareness of myopia among practitioners and parents needs to expand so that early identification and treatment can prevent much larger vision problems later in life.

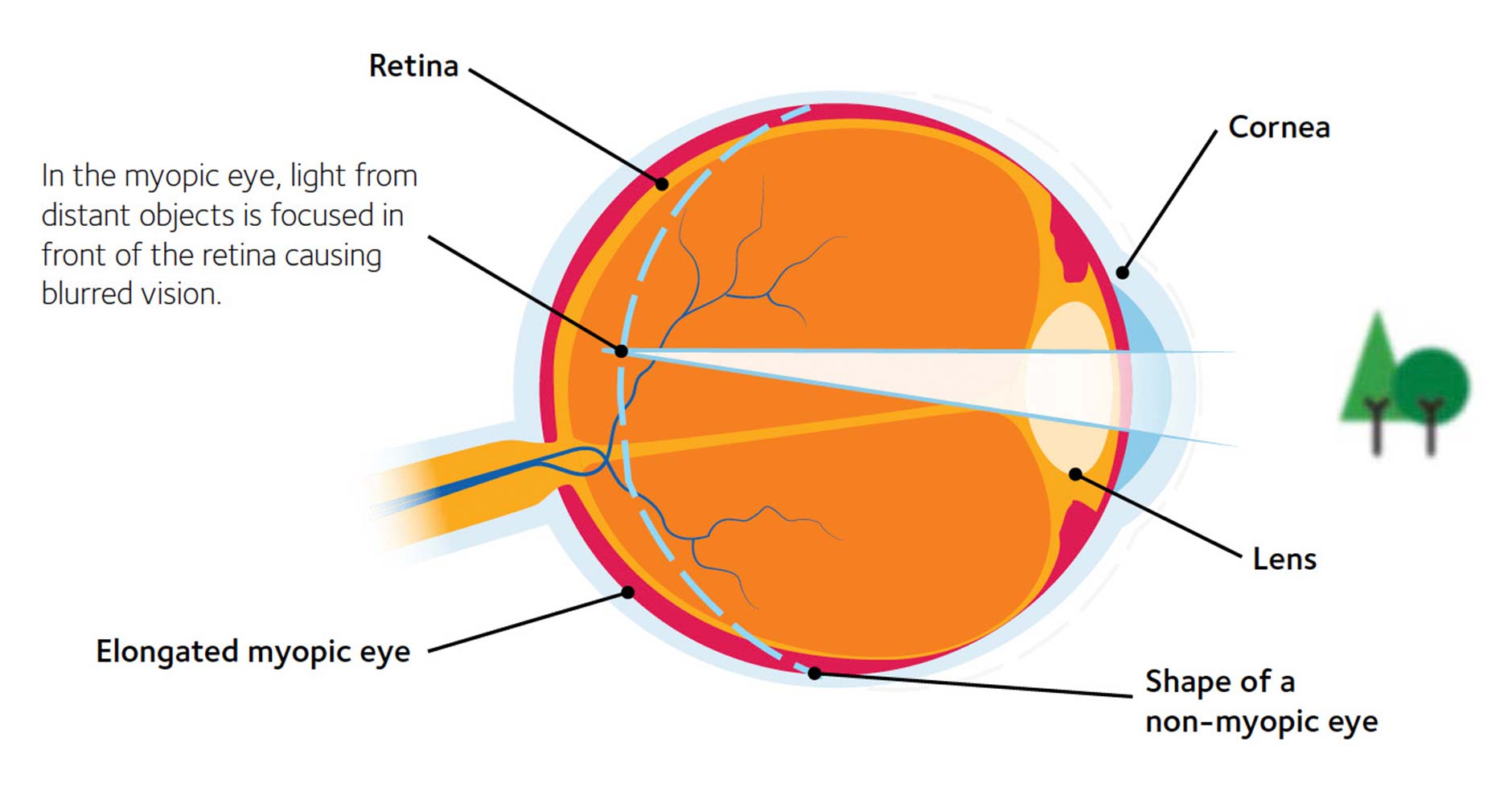

While the exact reason for the increase of myopia cases is unclear, lifestyle changes brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic could share the blame. Increases in the amount of entertainment screen time, confinement to an indoor home environment, and the switch to online learning have placed children in front of screens for a longer part of the day. An NIH-sponsored study published by Education Week indicates that children spend over an additional hour more on screens now than they did pre-pandemic. Looking at screens such as a computer, tablet, or phone for long periods causes the eyeballs to elongate and become nearsighted (myopic), causing distant objects to be blurry. In the US, myopia affects half of young adults, twice as many as 50 years ago, and can contribute to poor school performance, shortened attention spans, headaches, and eye strain.

If myopia in children is left untreated, serious life-debilitating and permanent vision problems such as retinal detachment, glaucoma, cataracts, macular degeneration, blindness, and more can develop. Untreated myopia conditions can result in severe economic losses for both the individual and the world in general. Lost productivity from untreated myopia and myopic macular degeneration around the globe was valued at an estimated $244 billion in 2015.

You might ask why, as an ophthalmologist, I am so interested in myopia progression. Myopia has affected me most of my life! By the third grade, at age eight, I had to wear thick eyeglasses in order to see at school and to play sports. I was very self-conscious of the glasses and hated to wear them on a basketball court or baseball field. It was impossible to see at the swimming pool. As a teenager, contact lenses were available for me, but because they were made of hard plastic materials I was never able to adapt to them. Thankfully now, more comfortable treatments are available, increasing patient compliance and resulting in a more positive corrective outcome.

When evaluating quality of life indicators utilizing validated questionnaires, studies show that the ability to see without contact lenses or glasses leads to improved self image

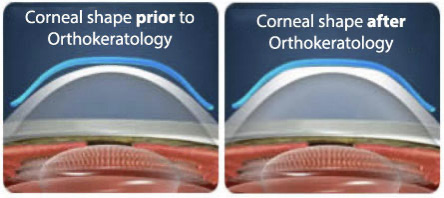

and self-confidence, fewer activity restrictions, less worry, and higher overall satisfaction with vision. This is probably no surprise to those of us who have had to be dependent on optical correction since childhood. Evidence-based myopia control treatments include a wide variety of options in addition to glasses. Daytime multifocal soft contact lenses, low-dose atropine drops, and a special molding technique using gas permeable contact lenses called orthokeratology (OrthoK) have all been shown to reduce axial length up to 50-60 percent in most studies. OrthoK can allow patients to reshape their cornea by wearing specially designed gas-permeable contact lenses, worn while sleeping, to temporarily and reversibly reduce refractive errors following lens removal in the morning. In my experience, I prefer OrthoK in young children starting at seven to eight years of age, as they adapt well to the nighttime wear. The gentle shaping of the cornea occurs overnight, and the child can then remove the contacts in the morning and be contact lens and glasses free throughout the rest of the day. The majority of the children that I treat adapt to this system and seem to tolerate it well.

I started fitting OrthoK lenses first in adult patients, who do extremely well with this contact lens modality. Patients in their 40s and 50s with developing dry eye disease or increasing allergy symptoms, like itchy or scratchy eyes, and who are failing with traditional daytime contact lens wear, do very well with OrthoK. I also fit teenagers beginning their contact lens journey with OrthoK lenses. Due to the nighttime wear, they love the freedom that these lenses offer them to participate in all sport activities and to prevent the sensation of a foreign body in their eyes during the day.

In summary, myopia is a combined disease of genetic predisposition and environmental influences. As the myopia epidemic continues to grow around the world, treatments and best practices to slow the progression need to be more widely utilized. If projections of 50% of the population having myopia by 2050 are correct, with 10% having severe myopia, we will be dealing with large numbers of older patients suffering from loss of vision from retinal detachment, macular degeneration, increasing and earlier cataract formation, and more severe glaucoma. The economic impact of lost productivity and dollars spent in caring for these seniors will be staggering! Two organizations that help coordinate this care in our area are the Bluegrass Council for the Blind and the Kentucky Department for the Blind. Early interventions that not only correct myopia, but also slow the excessive axial elongation and scleral stretching, are critical in minimizing the risks of complications that may lead to irreversible vision loss.

Myopia control options need to be prescribed with a custom-tailored approach by the eyecare practitioners working together with primary care offices, including pediatricians, family practitioners, and internists. All primary care offices should be doing vision checks on patients as early as possible. It is imperative for the long-term health of the eye that interventions are initiated in a timely manner. Throughout China, Japan, and Korea, programs are being started to identify and treat this growing myopia problem, but more still needs to be done, especially here in the Commonwealth, to save the vision of our next great generation.

Bruce Koffler, MD, can be reached at bkoffler@aol.com and at gdunn@md-update.com.